| Home |

Some random thoughts on enterprise and software systems architecture, and what comes into mind when dealing with these ...

Decisions, Decisions, ...posted Feb 11, 2024, 5:50 PM by Alar Raabe

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

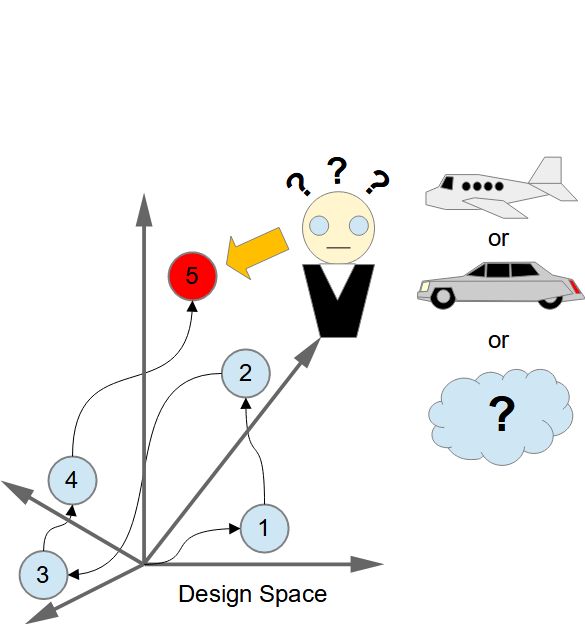

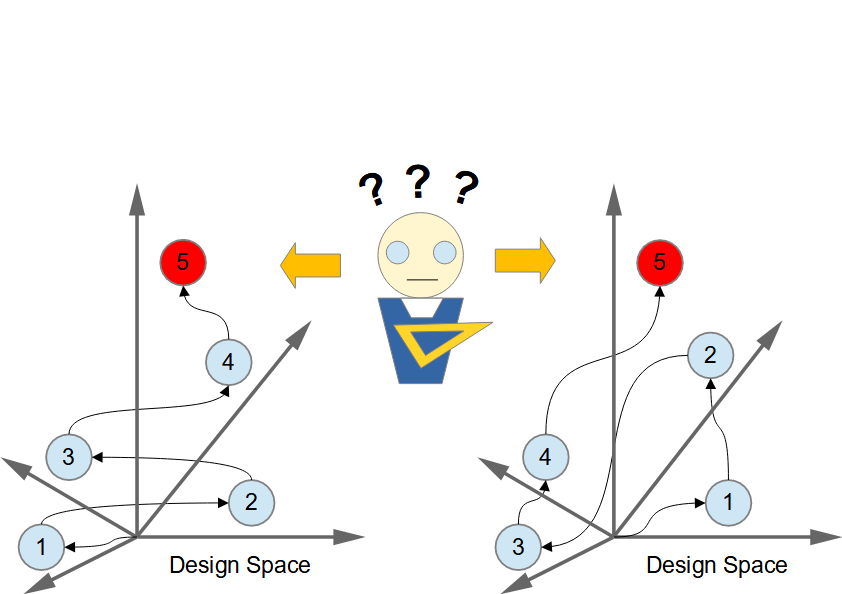

Designing an architecture can be seen, like any other design activity, as a set of decisions, where each represents a point in the design space (defined by all the design choices), and succession of these decisions can be viewed as a (search) path through the design space. This leads us to two important observations. It is not enough to document only the decisions that lead to the final design and not the design itself, because this would force the stakeholders, who need to know what the architecture is, to deduce it themselves. In case of agile/iterative development the order of design decisions (the paths taken through the design space) matters, because in some place of the design space the next possible choices could be constrained, so that it becomes impossible to reach the desired state. ...Designing an architecture (or “architecting”) can be seen, like any other design activity, as a set of decisions representing a path/trajectory in the design space (defined by all the choices that designer could make) that leads from the starting point to the final design (represented by a point in the design space), see H. A. Simon. The Sciences of the Artificial. The MIT Press, third edition, 1996. and D. Garlan, and M. Shaw, An Introduction to Software Architecture. On the kinds of design decisions and their attributes in the architectural design of software systems see P. Kruchten, An Ontology of Architectural Design Decisions in Software-Intensive Systems. There are two important questions related to this:

To that we must answer, that although it is important to record/document all the design decisions, this documentation alone will not be sufficient to document the final architecture, because this would force each reader to “replay” all the steps taken by the architect to be able to find out what the architecture is looking like (i.e. build itself the final architecture). Couple of random examples from such decision sets, which show this problem: OpenAttestation and ADR Tool. While this could be educationally a good exercise for introducing new team member to the architecture and the related reasoning, this will not be suitable for many other stakeholders, who need to see the whole architecture (as a possible input for their own decision making processes). Therefore we need also a description of the final architecture provided possibly from different viewpoints that correspond to the different sets of concerns of different stakeholders, see P. Merson, P. C. Clements, F. Bachmann, L. Bass, D. Garlan, J. Ivers, R. Little, R. Nord, and J. A. Stafford, Documenting Software Architectures: Views and Beyond, 2nd Edition, 2010 To that we must answer with the usual “answer from architect” – it depends! If we are doing the “dreaded” BDUF, then the order of design decisions is not important, because the steps from one point to another in the design space do not cost anything and any constraints on the steps between the two points in design space are due to the overall set of steps taken (due to the relationships between the design dimensions) independent of the order in which these steps are taken (see my thoughts on agile methods and architecture). But if we are trying incrementally build the design, making the design decisions as we go, then the order of design decisions becomes very important, because if certain design decisions have been implemented, this will rule out some other design decisions in the future (due to the aforementioned relationships between the design dimensions) – we can literally “paint our-self in the corner”. So to be successful in the agile (incremental development) and keep our options of choice as wide as possible, architect (or who-ever is the “master-builder”) must have the BDUF in his/hers “back pocket”, although there might be situations, where it’s better not to show this to the others who are involved in the journey. And yes, the systems must evolve and adapt to respond to the external changes, but this would be much more cost effective and faster (i.e. agile) with the architecture that allows such changes easily, not by changing the architecture of the system with every change of the environment. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Interfaces ... "question of life and death"posted Jan 28, 2024, 6:00 PM by Alar Raabe

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

All systems must have some way to separate and protect their internals from the external environment, because without such protection, leaving the internals open to the destructive forces of environment, the system will cease to exist very quickly. For open systems such boundary should not only protect the system, but also allow it to interact with its environment (e.g. pass information, energy and matter in a controlled manner and safely for the system). In the case of natural organisms such boundary is for example cell membrane or skin of more complex organisms, and in case of software systems such border is formed out of the interfaces through which the system interacts with the other systems. The same way, as with the natural organisms, it is also with the software systems – when the boundary of the system is broken (or lost) it leads to quick destruction (or death) of the system. ...All systems must have some way of separating and protecting their internals from the external environment, because without such protection, leaving the internals of the system open to the destructing forces of the environment, the system will cease to exist very quickly. For open systems such boundary should not only protect the system, but also allow it to interact with its environment – pass information, energy and matter in a controlled manner, which is safe for the system (so that nothing dangerous and potentially destroying will be able to enter the system). When the border between external world and internals of the organism is broken or removed, all organisms cease to exist (i.e. die) and will be decomposed – same is the case with the software systems, and to be able to talk about a specific software system at all, we need to define (and control over time) the system scope (i.e. define what are the parts of the software system and what are not). Additionally to allow software system to interact with its environment in a controlled manner, we need similar mechanisms like in the case of other open systems (incl. natural organisms), which allow software system to exchange information with the external environment in a controlled and safe manner.

If software systems need to maintain the control over their internals and avoid destruction/corruption by external forces, they need to enforce that all exchange of information between the software system and its environment happens through the well-guarded and strict interfaces. As soon as the interfaces are bypassed and software system internals are directly accessed and manipulated from its environment without any restrictions, or software system internals are accessing ts environment without any control, the software system starts to “die” (i.e. gradually corrupt to the point where it cannot be maintained anymore and must be replaced by some other system). What is an interfaceThere are many definitions for the interface:

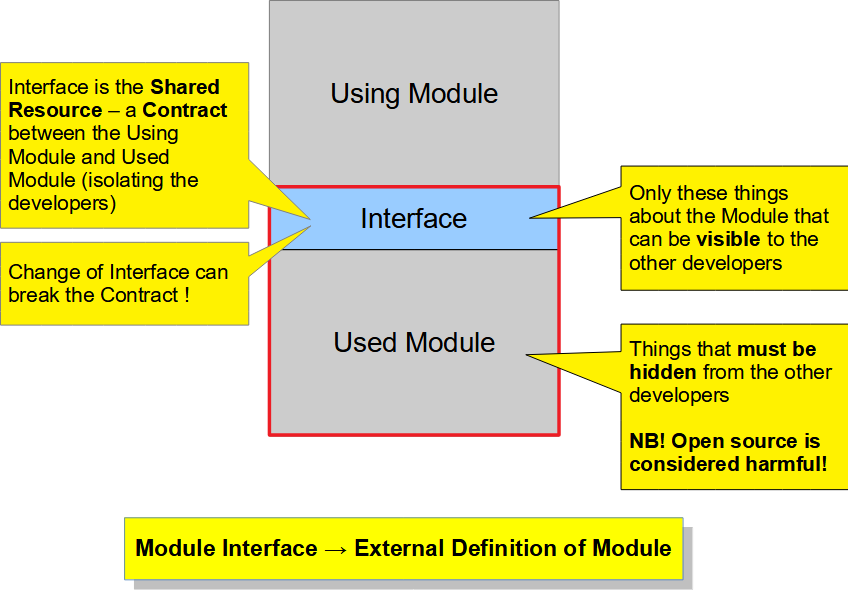

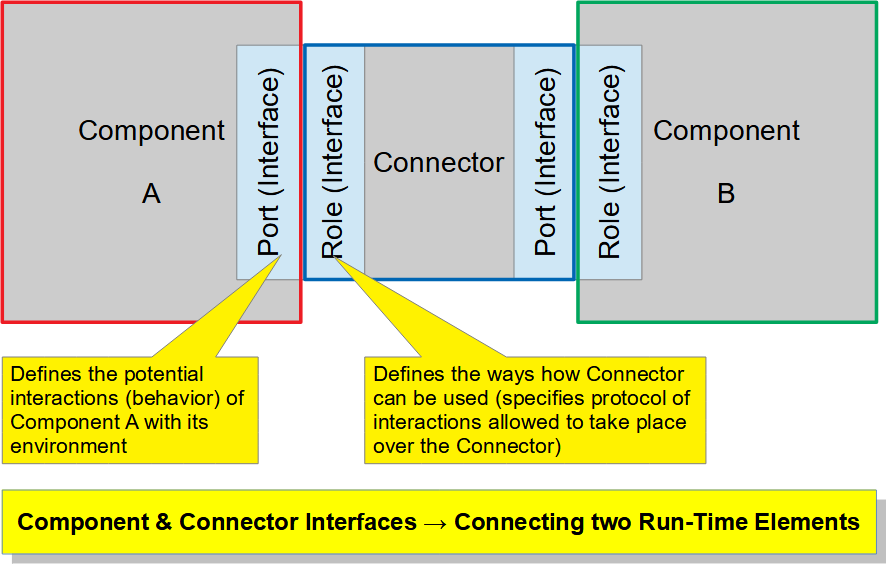

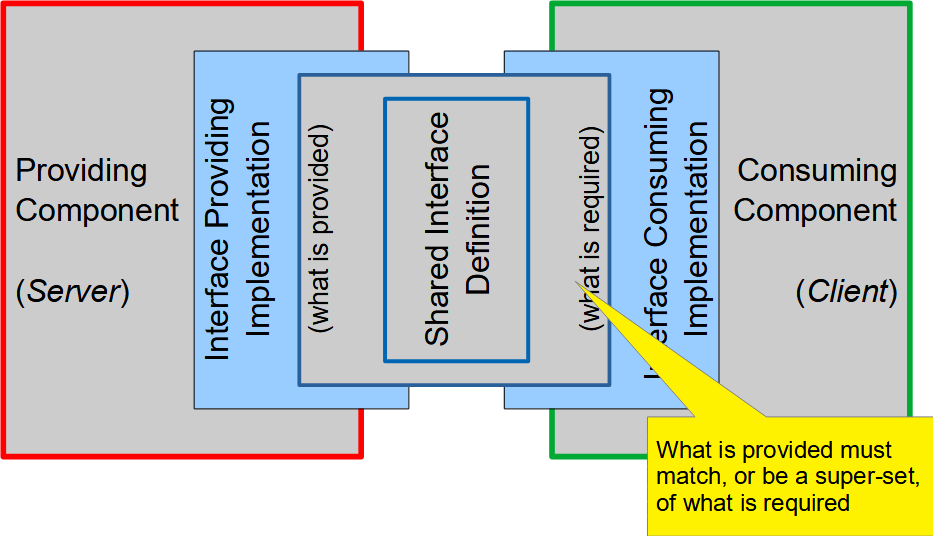

As we can see, interface is most often seen as the boundary of a system or a special component, through which the environment can interact with the system and which is abstracting (or mediating) the behavior of the system for the environment (i.e. interface is providing a “language” and the mechanism to communicate with the system and request/access the services it provides). From the differences of these definitions it comes clear that in some sense the interface can be also viewed as a contract between two systems, because it embodies a set of conventions which both systems must follow for the interaction to be successful. This duality comes from the fact that there are two kinds of (architectural) structures in the software systems [CMU SEI], which should not be mixed:

If we look at these structures, then both these have interfaces, but:

There could be only one module interface of given type (signature) per one module, but there could be many component and connector interfaces of same type per components and connectors. Following rules apply for the component and connector structures:

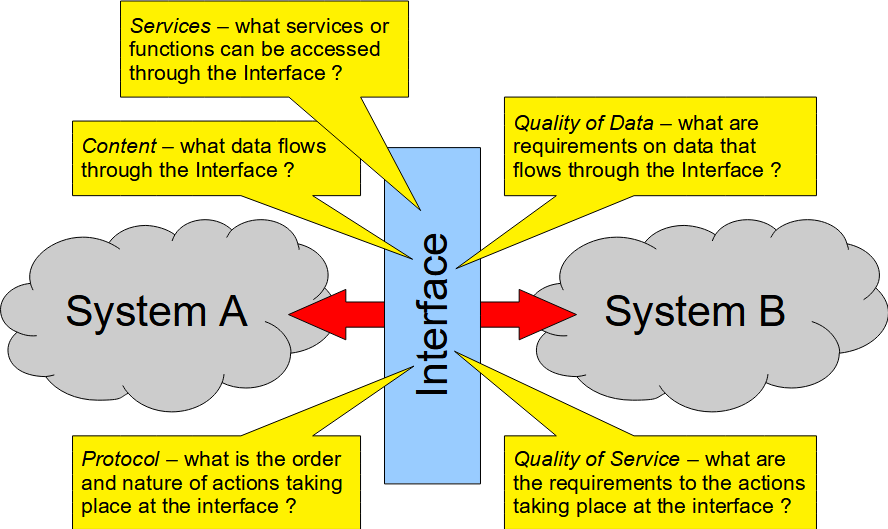

Characteristics of an interfaceThere are several important characteristics that an interface as the boundary and a contract between two systems must define. When looking at the interface as a contract between two systems, interface must answer the following questions:

All these questions need to be answered by the description of the interface. Although in some sense the interface, which connects two systems together as a contract between those systems, is positioned between these two systems, it still usually belongs to one of these systems. Which of the two systems “owns” the interface and therefore defines the contract between two systems, is the decision that the systems designers have to make:

Why we need interfacesAs was described above, module interfaces are needed for communication between the developers – defining these things that are visible to the developers using the module, while hiding all other information about the module, isolating this way the developers, who will use the module from the developers who will develop and maintain the module. Component and connector interfaces are needed to control the information and control flows between the elements of the running software system, and this way support isolation of components, modifiability, reusability, and help manage the complexity in the run-time structures of the software system. The good interface isolates the software system from the external environment and protects its internals, additionally the good interface (especially the module interface) is easy to understand for the developers, it provides the model, that helps to understand what services/functions the software system could provide and how those services/functions can be accessed. An interface description is kind of “problem-oriented language” for using the software system. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Who has "Big Picture"posted Dec 3, 2023, 8:30 PM by Alar Raabe

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

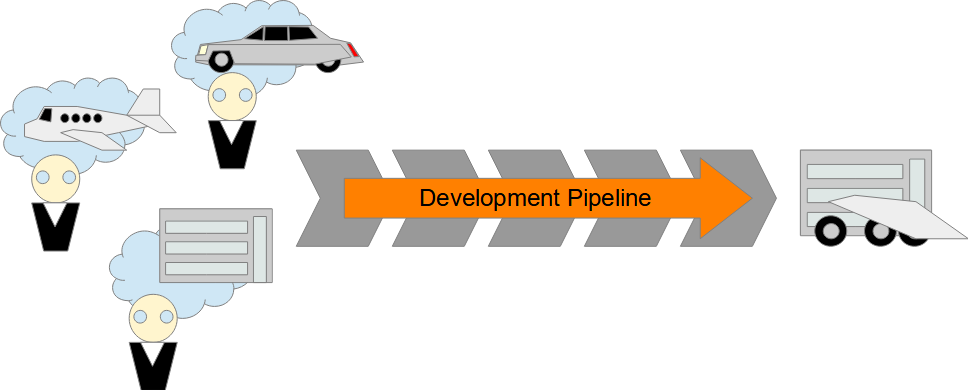

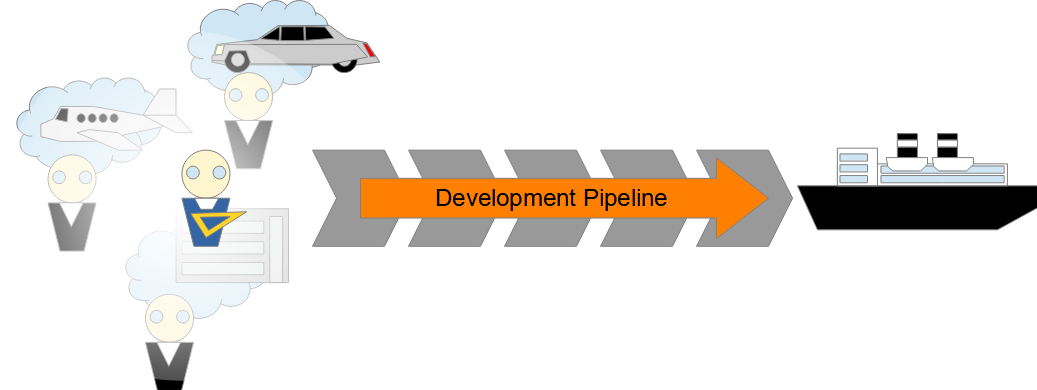

During the last years, the agile movement, has transformed IT development organizations into very efficient engines, which can deliver the tasks “thrown at it” with a great speed and efficiency, but the outcome of this efficient engine is only as good as is the input. But when there are different competing views in the organization about what is needed to be built, and the sponsors of all these competing views generate parallel streams of inputs to the IT development engine(s), having in their minds their own target(s), then the output produced would be a chimera – a mix of the pieces from the different targets, put together in the order defined by which sponsor at which time had a strongest bargaining/prioritization position. To avoid building very efficiently a “Big Ball of Mud”, employing the agile IT development requires, that business will build their own strong business analysis and development organization, capable of developing and maintaining the holistic picture of the target, needed to support execution of the business strategies of the enterprise, and to divide it into the suitable size pieces, which could then be in correct order fed into the IT development pipeline/engine. ...During the last years, the agile movement in the IT development, has transformed IT development organization into very efficient pipeline or engine, which can develop software and deliver the tasks “thrown at it” with a great speed and efficiency, but the outcome of this efficient engine is only as good as is the input. But when there are different competing views in the organization about what is needed to be built, and the sponsors of all these competing views generate parallel streams of inputs to the IT development pipeline(s)/engine(s), having in their minds their own target(s), then the output produced would be a chimera – a mix of the pieces from the different targets, put together in the order defined by which sponsor at which time had a strongest bargaining/prioritization position. Even if each of the pieces of this “Big Ball of Mud” [see http://www.laputan.org/mud/mud.html#BigBallOfMud] would be build according to the highest engineering standards, the result would not be fit for executing the enterprise strategies, and whole enterprise landscape would be difficult to improve or evolve. If previously IT development included also the business analysis and architectural design as part of IT development, where the first stages of the development project, analyzed the full picture and developed the full understanding of what needs to be built, then in agile world this is seen as waste (see YAGNI [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/You_aren%27t_gonna_need_it]) and pushed out of the IT development, hoping that this will be done by somebody else before development starts, and that if developments lead us to the dead end, we can always backtrack and redo (refactor) everything. Because it would be possible frequently to refactor whole enterprise, and because the big picture of the target this is required to avoid “going with great speed and efficiency to nowhere”, somebody else, than IT, in the organization must develop and maintain this big picture. To avoid building very efficiently such a “Big Ball of Mud”, employing the agile IT development organization requires, that business will build their own strong business analysis and development organization, which is capable of developing and maintaining the holistic picture of the enterprise target, which needs to be built to support execution of the business strategies of the enterprise, and also be able to divide this target into the suitable size pieces, which could then be in correct order (to avoid for example sunk costs) fed into the IT development pipeline/engine. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Models vs Illustrations in Software Engineeringposted Nov 19, 2023, 5:45 PM by Alar Raabe

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

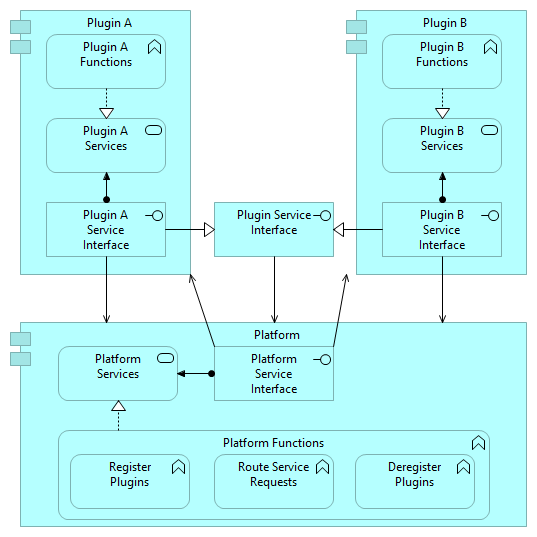

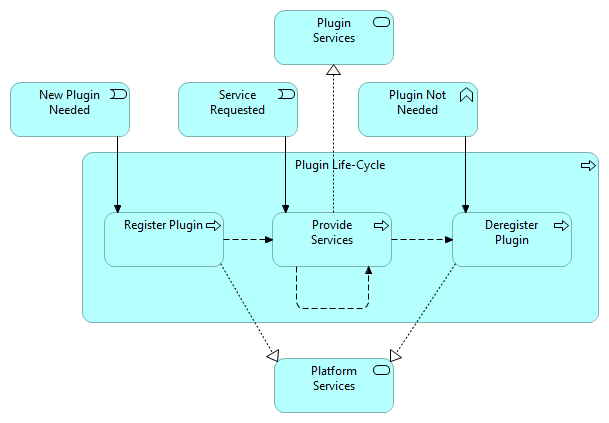

There is a constant discussion in software engineering community about the use and usefulness of models/modeling, but often in these discussion, visual representations of models are mixed with the illustrations. So what’s the difference? The main purpose of model in software engineering is to answer certain questions about some object (to be built or studied), but the purpose of an illustration is to communicate certain message (which could be one of the answers provided by some model, or something else). Both are needed, but for different purposes – visual representations of models generally do not serve as good illustrations, and illustrations do not serve as (good) models. For automating the software engineering activities, the models need to be machine-readable, but the illustrations need always be human-readable. ...There is a constant discussion in software engineering community about the use and usefulness of modeling in software development, but often in these discussion, visual representations of models are mixed with the illustrations. So what’s the difference between an illustration (a picture) and a visual representation of a model? The main purpose of model in software engineering (as in many other engineering disciplines) is to answer certain questions about some object (to be built or studied), but the purpose of an illustration is to communicate (make clear) a certain message (which in case of engineering can often be one of the answers provided by some model or something else). Both are needed, but for different purposes, and therefore the properties of the good model are very different from the properties of a good illustration – visual representations of models generally do not serve as good illustrations, and illustrations do not serve as (good) models. Do not blame an illustration, if it does not give answers to your questions, and do not blame a visual representation of a model, if it does not communicate a clear message! An example of illustration of the idea that we should build a platform that allows a set of plugins to cooperate, could be following: Although such illustration could convey rather well the main message, it does not help us to answer the questions of what to build as a platform, how plugins must be built, and how their interactions with the platform and between themselves would happen, as many other questions that we would like to get answers before we even start building such thing. If we want to have answers to these questions or record the design decisions that we have made to be recorded precisely to allow different teams that might be involved in the building of platform and plugins to reach the end result that fulfills all the requirements, we need a model of the platform, plugins and possibly also model of their interactions. Such models could have following visual representations: First describing the static structure of the platform and two plugins (providing answers to the questions that are related to to the development and building of such system), and second describing the dynamic behavior of a plugin, it’s interaction with the platform (providing answers to the questions that are related to the ability of such system to work as required). Because this function of the model, the most important properties of a model are correctness, consistency and completeness – model must act as a single source of truth for the development activities. When we need to automate the software engineering (or any other engineering discipline), another important property of the models is existence of digital, machine-readable representation, which is required to be able to process models with different analysis and development tools – human-readable representations of the models does not have to be even exist. The illustrations in other hand need always always be human-readable. The whole activity of modeling (incl. building and analysis of the models) is very different from the activity of creating illustrations – different skills and tools are needed for both. If there exists a model of an object, then also various illustrations could be created, but because the good illustration is not just representation of facts, but for better communication, must contains aspects that influence emotions of the intended audience, this is rather complex task, which requires artistic talents, and therefore has been more difficult to automate, than just creating a visual representation of some information taken from the model. By trying either to use illustrations as models, to answer questions, or visual representations of models as illustrations, to communicate something, neither of the goals will be fulfilled, and we will be disappointed in the results. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Levels of Business Processesposted Nov 5, 2023, 8:50 PM by Alar Raabe

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

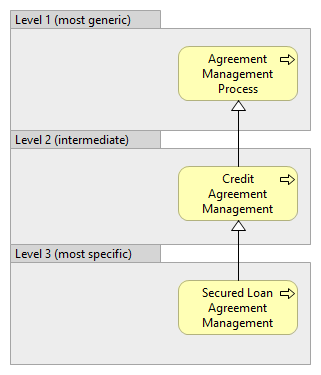

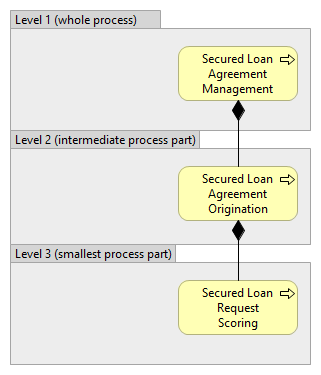

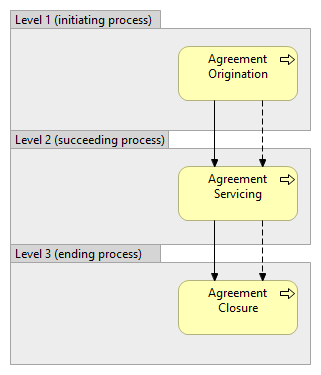

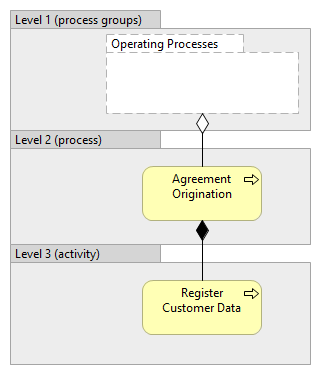

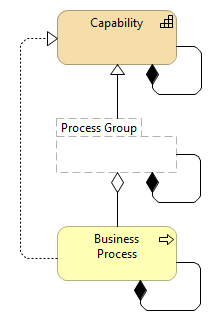

When talking about the levels of business processes, it is important to clearly state which relationship between the business processes is taken as basis for separating the business processes into different levels. When business processes are combined into same hierarchy with other modeling concepts, it would be important to clearly identify on which level which modeling concept resides. ...People often talk about the levels of business processes, but based on the possible relationships between the business processes according to OMG BPMN and Open Group ArchiMate standards, there could be several different relationships of hierarchical nature, between the business processes, which all could form levels. Let’s look at the examples of two such relationships that allow forming of hierarchies (like specialization/generalization and containement): There could be also other relationships between business processes, which allow formulation of levels, although in these cases the relationships themselves would allow forming of more complex networks, not only hierarchies, and therefore notion of levels gets even more unclear. If talking about the levels of business processes it is important always clearly state which relationship between the business processes is taken as basis for the particular levels, otherwise the meaning of being in one or another level is lost. If other modeling concepts (like groups/categories of the processes or activities or something else) are mixed into the hierarchy, then we cannot anymore talk about the levels of processes. For example on following picture, only second level of hierarchy contains processes, therefore we cannot talk about first or third level processes: Therefore, when business processes are combined into same hierarchy with other modeling concepts, it would be important to clearly identify on which level which modeling concept resides. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

What to focus on in Business Capability Mapposted Oct 29, 2023, 9:30 PM by Alar Raabe

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

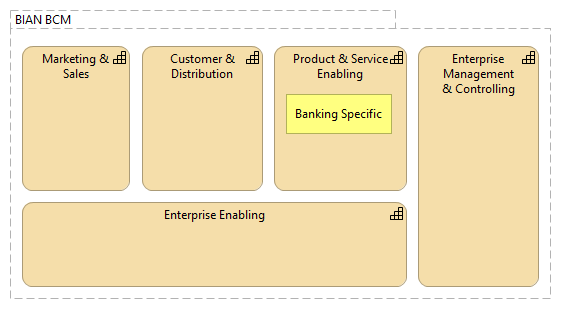

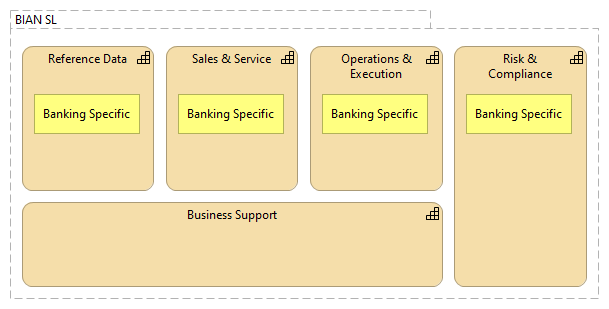

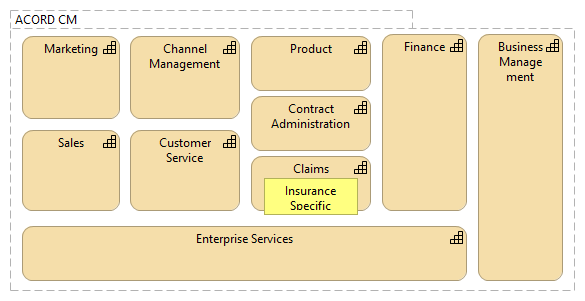

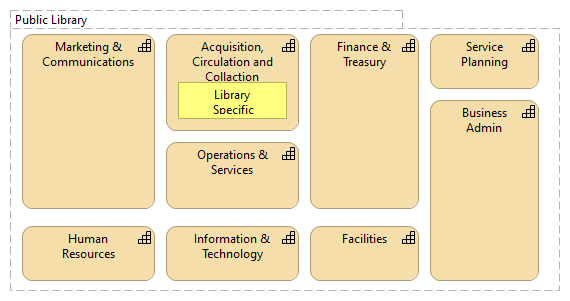

There seems to be two different schools of defining the business capability maps/models – for same business area/domain one produces very generic domain-independent business capabilities and another much more domain-dependent business capabilities. If the main purpose of business capability map/model is to support the strategic thinking, then it seems strange to abstract out all the domain specific traits from this tool, because the result would not have “high enough resolution”, to see the strategically important things in the business capabilities. Therefore, although it would be easier to create more generic business capability map/model, the more useful business capability map would be specific to the business domain (or even to the particular enterprise). ...According to the WikiPedia, business capability maps/models are one of the most widely used Enterprise Architecture artifacts (see Enterprise Architecture Artifacts). If looking at the different business capability maps, then an interesting thing sticks into eye – some business capability maps of the same business area/domain are more generic than others, up to the point, where only small part of the business capabilities, if any, are business-specific. Although the definitions of business capability are rather well converging (see various definitions in Business Capabilities vs Business Processes) into „an ability or capacity that a business may possess to achieve a specific purpose”, there seems to be two different schools of thought in respect of what is the purpose of business capability map/model and how to identify and define the business capabilities. This is especially well illustrated by the change that happened in BIAN between versions 6 and 7 (see BIAN v7.0 Release Notes), when additionally to already existing business capability map, called in BIAN “Service Landscape” (SL) a new business capability map (BIAN “Business Capability Model”) was added, and (business) service domains, which previously were considered as „business capabilities” (see BIAN How-to Guide and Design Principles & Tehniques) were re-considered/-purposed as „business capacities”. Therefore we could consider both models as actually business capability maps, but created from different viewpoint (using different method). The reasoning behind these differences is given in the BIAN white-paper on BIAN BCM alignment with the BIAN SL (see BIAN Business Capability Model Statement of Alignment with the BIAN Service Landscape): The BCM can be considered as an external perspective. It does not attempt to reconcile 'what needs to be done to create value' with 'what is needed in terms of the specific internal functional capacities' (put another way: a BCM defines 'what', not 'how'). The BSL conversely is more of an internal perspective that defines all of the essential functional capacities that are required to support any of the intended business activities. But in contrast, the BSL does not formally associate the use of its identified functional capacities with any specific business value creating context. If we now compare these two maps/models, we see that the BIAN BCM isa much more generic than BIAN SL (i.e., much smaller part of the Business capability model deals with the banking-specific functionality ): That seems counter intuitive, if we think that the purpose of BIAN BCM is to support the strategy work, that this particular model is actually less banking specific than BIAN SL. The same school of thought is also visible in the ACORD Capability Model (see ACORD Capability Model) and in the example for business capability map/model for public libraries (see A Brief Introduction to Business Capabilities and Capability Model). All these three examples consist mostly of the same business capabilities, which any enterprise or institution would need, see: Even if we could agree that strategies for banks and insurance companies could be similar, then I is difficult to see that a strategy of a public library would be similar to bank or insurance company strategy, although the business capability map, supporting the strategy work, might let us think that way. Obviously the cause is over-generalization, which on certain level of abstraction makes all enterprises and institutions (in western culture context) similar, but that will not help to make strategic analyzes or development of the strategy (especially the strategy that allows enterprise to distinguish itself in the marketplace). If the main purpose of business capability map/model is to support the strategic thinking, then it seems strange to abstract out all the domain specific traits from this tool, because the result would not have “high enough resolution”, to see the strategically important things in the business capabilities. Therefore, although it would be easier to create more generic business capability map/model, the more useful business capability map would be specific to the business domain (or even to the particular enterprise). |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Business Capabilitites vs Business Processesposted Oct 15, 2023, 5:30 PM by Alar Raabe

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

From time to times the question of “what’s the difference between business capability and business process” pops up, although these two are rather established concepts. It seems to me, that the confusion might be caused due to the introduction of groups/categories of business processes by some methodologies (not always clearly stating the difference), which in some cases might correspond to the business capabilities. Business capability, describing WHAT business needs to be able to do, implies that there might be some business processes, describing HOW business should do that, but not always – therefore it makes sense to keep business capabilities separate from, but connected to the business processes. ...From time to time, I see that in the discussions about the business architecture part of the enterprise architecture, somebody again raises the question “what is the difference between the business capabilities and business processes?”. Although this difference must be rather clear from the most widely accepted definitions (see below), and has been stressed in many enterprise/business modeling frameworks and methodologies that the capabilities define WHAT business needs to (be able to) do (implying all that is necessary for that), and processes define HOW that must be done, for some reason there is still some confusion. It seems to me that this confusion arises mostly from these enterprise/business modeling methodologies, which see the business processes as the primary element in the business architecture or concentrate on the process architecture. In these methodologies (like APQC, ARIS, Cordial, …) business process together with the categories and groups of business processes are included in a common decomposition hierarchy of business functionality, bringing the confusion and difficulties described in Dividing the Enterprise. Sometime the confusion is further deepened by the naming of these categories and groups, as can be seen from the following table, where the actual business processes are on the different levels (and unfortunately not always named as “business process” or even “process”):

It is common that in such methodologies both WHAT business needs to do and HOW it does that, are bundled together, although it is clear that WHAT business needs to do could be implemented/realized by many different ways of doing this (i.e., many different business processes), and in some cases it might be not known/decided yet. Because the purpose of business processes is to implement/realize the business capabilities, and because for a given business capability there could be zero-to-many business processes, business capabilities are actually a good choice to group together a set of business processes, the same way as business capabilities are a good choice to group together also other enterprise/business architecture elements, needed to implement/realize them (see Open Group TOGAF Business Capability). Some definitions:

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Is Architecture Abstract or Concrete?posted Oct 1, 2023, 11:15 PM by Alar Raabe

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Many authors are claiming that architecture is abstract, but if we follow the well-known definitions of software architecture, then we see that although architecture is conceptual, it is not always abstract. Because architecture is embedded in the system (and can be recaptured), influences the actual qualities and the behavior of the (software) system, and architecture is something that can be acted upon by changing the system. ...Many authors are claiming that architecture of (software) systems is abstract – a good example is ISO standard on systems architecture description (see ISO 42010) (where it is also added that “architecture is … not an artifact”). According to the Cambridge Dictionary abstract, being an opposite of concrete, means “existing as idea, feeling, or quality, not a material object” (see Cambridge Dictionary : abstract). One of the important characteristic of the abstract things is that these are considered non-causal (see Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy) – that is, abstract things cannot be cause of anything. If we follow the rather largely accepted definition of (software) systems architecture (for various definitions, see for example CMU SEI), according to which the architecture has been defined as consisting of following three parts:

Then we cannot always treat the architecture of (software) systems as abstract, because architecture of an existing (software) system is embedded in the structure of that system (at least this part of the architecture that is consisting of the elements and relationships), and therefore it is real/concrete in the same way that given system is real/concrete. Architecture of a (software) system exists “within” the (software) system, and can be observed and recaptured/recovered from the (software) system after it is built, even if the specific description of the architecture, which was used during the building of that (software) system is lost. We can have different perceptions or conceptions of architecture of a (software) system, and we can describe these perceptions or conceptions in different ways from different viewpoints and on different levels of detail, but that does not make the architecture itself abstract. But because the (software) systems architecture is based on the ideas and principles that define how to divide the system into the components and connections, then we can say that (software) systems architecture is always conceptual (according to Cambridge Dictionary, conceptual means “based on the ideas or principles”, see Cambridge Dictionary : conceptual). Only in the case when the actual (software) system is not yet built (i.e., not yet existing), the architecture of such (software) system, described in the plans and design documents, can be considered abstract (i.e., existing only as an idea). The important implication of (software) system architecture not being just an abstract, but a real/concrete thing, is that:

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Dividing the Enterpriseposted Sep 24, 2023, 10:45 PM by Alar Raabe

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

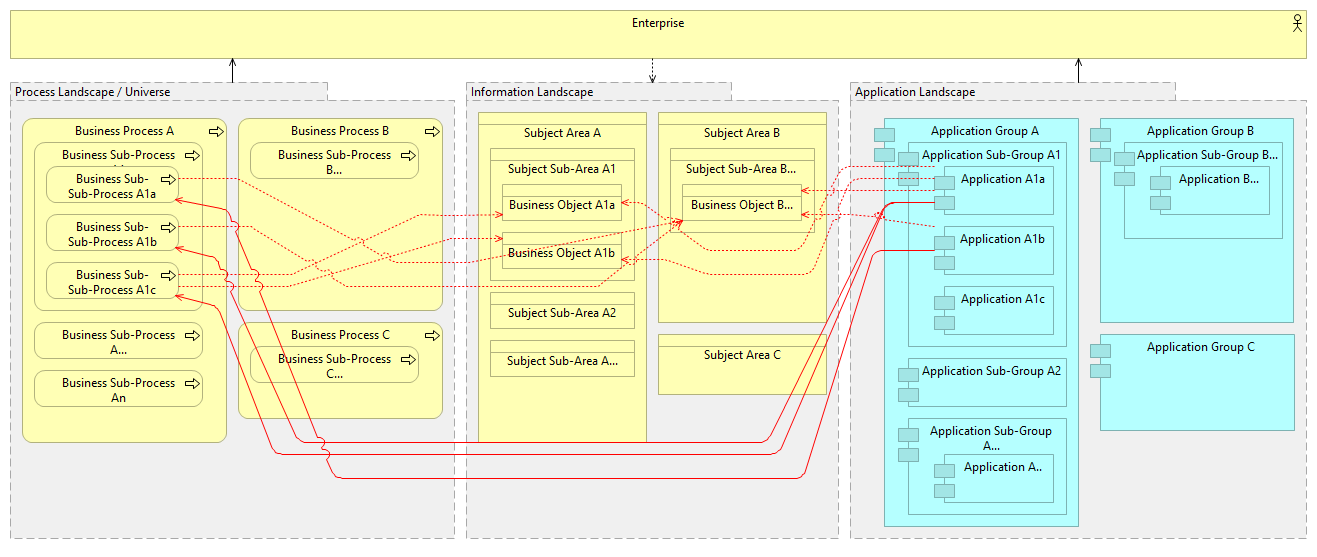

“Divide et Impera” – break down a problem into two or more sub-problems of the same or related type, until these become simple enough to be solved directly. Because enterprise is usually very big and complex system, we need to decompose it – divide it into manageable pieces for any analysis or design activity, and for efficiently organizing and managing the multitude of the elements that are identified and used for describing the enterprise from various viewpoints. ...It is usual, that different disciplines, which deal with the analysis and design activities of an enterprise from different viewpoints and for different purposes, divide the whole enterprise based on their primary interests and according to the main methodologies in their area, organizing the elements that describe the enterprise according to different criteria. This could be illustrated for couple of such disciplines (process modeling/management, information modeling/management and applications modeling/management) for example as follows: Because for both analysis and design these elements are usually needed to be viewed/described in their context(s) (e.g. processes create and use some information and are supported by certain applications; applications master, provide and consume certain information; etc.), this leads to the need of connecting the elements identified/used by different disciplines, to avoid creating several separate and possibly inconsistent views on the same enterprise. This all leads to the following problems:

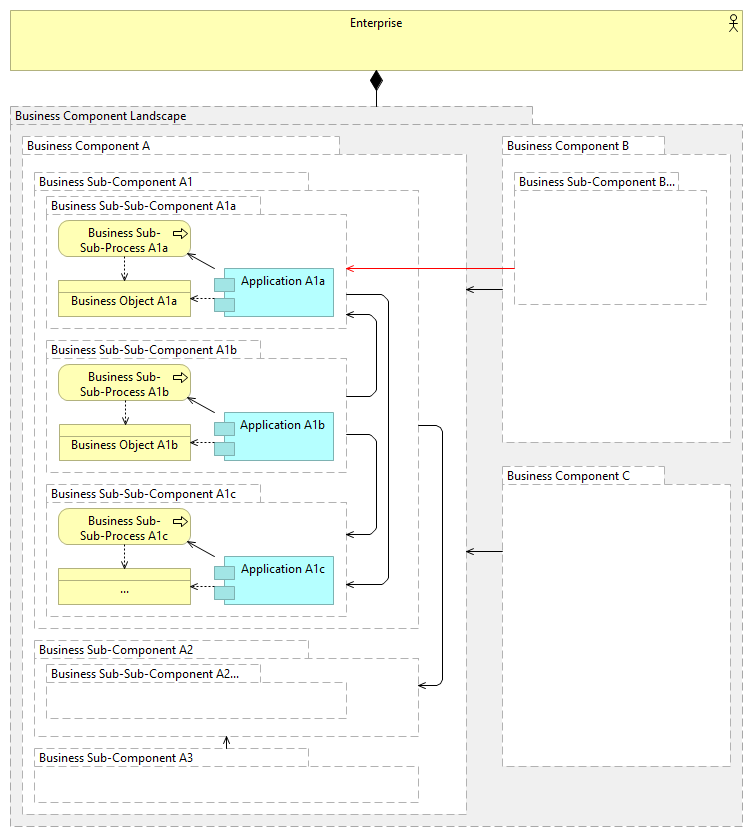

To avoid all these problems we should decompose the whole enterprise only according to one criterion, and do this recursively, breaking the enterprise into the self-similar smaller pieces (self-contained parts of the enterprise), which could be thought of possible to completely outsource to some other enterprise (if needed). Only at the final level of decomposition, in the leafs of such decomposition hierarchy other elements, that describe the enterprise (or parts of an enterprise), appear. Therefore such decomposition will collect together and organize according to the same schema all the various elements used in the analysis and design of the enterprise. Such decomposition could be represented as follows: And this leads to the following benefits:

Such decomposition method has been earlier described and employed for example by:

Although in some cases business capabilities are defined nearly the same way (see Archimate 3.2 Capability and TOGAF Business Capability), many business capability models are built in such a way that business capabilities in these models cannot be viewed as self-contained parts of the enterprise (which could be possibly outsourced), therefore not representing holistic parts in the recursive decomposition of whole enterprise. A good description of the problems involved by negotiating such business capability model with the decomposition of the enterprise done according to the way, described above (i.e., Service Landscape) is provided lately by BIAN (see BIAN BCM Relationship with BIAN Service Landscape). … |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Architectural changeposted Aug 21, 2023, 11:48 PM by Alar Raabe

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

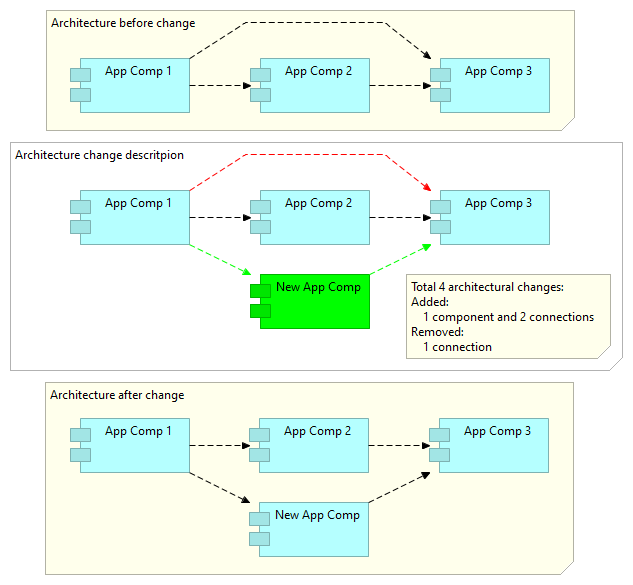

Lately the question of what is an architectural change of a software system, has popped up in various discussions. The answer to this question guides the involvement of architects in systems development, and architecture governance and documentation. I would say, that if we base on the well-known definitions of software architecture, only certain kinds of changes could be considered as changes of architecture, independent of how big in terms of effort the change is. ...So, what we should consider as an architectural change of the software system? In many previous works on software systems architecture, the architecture has been defined as consisting of following three parts:

For example the definition of (software system) architecture, adopted by many standards organizations, the (software system) architecture is "fundamental concepts or properties of a system in its environment embodied in its elements, relationships, and in the principles of its design and evolution" (e.g. ANSI, IEEE and ISO). That definition, which is revolving around building a structure for certain purpose, is well in sync with the definition of architecture in civil engineering (by which the discipline of software architecture is inspired), where architecture is mainly seen as “the art or practice of designing and building structures and especially habitable ones” [Merriam Webster]. Although the latest incarnation of the ISO standard on systems architecture description [ISO 42010:2022] has for some reason dropped “elements and relationships” from the definition of system architecture, I will stick with the previous definition, as the elements and their relationships of the software system, which representing how the software system is built, are the most important things to consider in the context of the change of the system. To clarify what is the architectural change, we need to bring in one more concept – the architecture style – which represents what is architecturally common to a family of software systems, being a kind of design language for the software system architectures, and is usually seen as consisting of following things [Garlan & Shaw, Shaw & Clements and SEI CMU]:

Well known architecture styles are for example: data flow (a.k.a. pipes and filters), data centered (a.k.a. repository) repository, layered systems, etc. [Garlan & Shaw]. Now, based on these definitions, we can define what we mean by the change of architecture (or architectural change) of the software system. Following kinds of changes of a software system can be considered as changes of the architecture (or architectural changes):

Two first ones are simple and local, because they do not affect the architecture style of the system, but the last one is in nature complex, as it can affect the architecture of the system globally, and can lead to the change of the software system architecture style (e.g. by changing set of allowed component and/or connection types, and the way how the software system can be built using the components and connections). Simple description of architectural changes could be given by coloring the corresponding elements on the diagram ("green" for additions and "red" for removal): Defining architectural change this way means for example, that if the existing rules and principles of a software system architecture allow implementation of components on several platforms, then reimplementing an existing component on different platform, allowed by the architectural rules and principles, is not an architectural change. But if the new platform is not yet included into the architecture rules and principles and will be by this change, then this change is an architectural change. If the change is such that the meaning/purpose of one component or connection has been changed, then this must be considered as being equal to the removal of the old component or connection and introduction of a new component or connection. A good example of the later case is (a rater usual case of) change of the core schema of a central database (or repository) of a repository-centric system in case there has not been established any interface schemas for connections with the processing components of the system or otherwise insulating those from the central database (or repository), we in architectural sense actually replace one (in this case very central) component and all its connections to all other components. Therefore one, seemingly small, change becomes actually a massive architectural change, affecting whole system (causing cascading changes and possibly leading to many unanticipated side-effects). If we consider the simple measure of the complexity of software system the number of components and connections (see Complexity in/of the enterprise architecture), then this way of treating the architectural changes allows us also simply measure the effect of the changes to the complexity of the architecture, by the added/removed components and connections. Although the reasoning above is about the architecture change of the software systems, the formulation of systems architecture as a set of components, their interconnections and rules of composition, does not rule out any other types of systems -- so we can apply same definition of architecture change also to the business system (or to the combinations of both business and technology systems). |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Thoughts on architecture and agile methods (in the example of SAFe)posted Feb 07, 2023, 10:53 PM by Alar Raabe

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Agile software development pactices try to embed the design of the sofware system architecture into other development activities, instead of doing it as a separate activity. Although the software system architecture can be developed in various ways, there are some implications if this happens incrementaly and is driven by random stream of requirements. ...So what's the relationship between architecture and agile methods, if there's any? If we take the definition of (system) architecture adopted by many standards organizations, which is "fundamental concepts or properties of a system in its environment embodied in its elements, relationships, and in the principles of its design and evolution" (e.g. ANSI/IEEE/ISO 42010), then we could rest assured, that whatever is the method or way of developing the software system, it will always have an architecture – that is, architecture will emerge when we develop the software system. From the studies of the different styles of software architecture we can see that software systems, that peform the same function, can have rather different architectures – so why to bother? The problem is raised, because apart form the function that software system performs, we often are interested of some other properties of the software system (usually specified as non-functional requirements towards the software system), and because software system architecture is the cause of many important properties of the software system, which are usually requested by several stakeholders. The core of the agile methods is to design and build the software systems piece-wise, but while the functionality of the software system is usually possible to divide into pieces or decompose rather easily, the software system architecture, being a set of global structures, affecting the software system as a whole, does not lend itself to such treatment. Usually some global structures, that define the software system architecture need to be first developed and completely built (at least up to certain level of completeness), to be able to implement the pieces of the functionality (i.e. system functions). SAFe represents the larger pieces of the system functionality (or system functions) by the capabilities, which themselves can be decomposed into smaller pieces of functionality, called features (see Features and Capabilities in SAFE). Admitting the insufficiency of the emerging architecture alone and agreeing to the need for the intentional architecture of the software systems, SAFe proposes an Architectural Runay as implementation of software system architecture (i.e. the code and infrastructure needed to implement the features), which can be itself evolved/extended by implementing the Enablers. So far so good, but to be able to divide the work so that we can build first just a part of the software system architecture, needed for a set of features, we need to be able to map these features onto the software system architecture, for which we need the full architecture designed first. Therefore, in the best case, we can build the implementation of the software system architecture piece-by-piece, but before that we need to design it as a whole. Another slight complication is the global nature of the software system architecture structures – if for any reason we need to change the software system architecture in such a way that is not supported by the extension mechanisms of the existing architecture of the software system, we need to implement the new software systems architecture an then re-implement/-build all the features that have been built so far (because the system architecture defines how the features are built). All development teams try to avoid later as long as possible, as a very costly exercise. Another complication arises from the fact that, if the overall software system will be designed and developed incrementally as a response to the stream of requirements stated by the stakeholders, the software system architecture will very much depend on the order in which these requirements arrive. For example if we build the communication system (e.g. a chat system) and the requirement for high security of personal information and communications is received within the first requirements, this might lead to the selection of an architectural style of independent components, where none of the components has complete knowledge of all the users and communications within the system, but if this requirement is not received early enough, then it would be natural to select the architectural style with central reporsitory for users and communications. When now the requirement for high security of personal information and communications arrives, there could not be possibility to completely re-implement the system according to different architectural style, and therefore architects might select compensating techniques, adding encryption fo a central datastore, leaving the architecture of the system same (which will not meet the requirements in best possible way). |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Using ArchiMate for modeling ...posted Nov 9, 2020, 10:08 AM by Alar Raabe

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

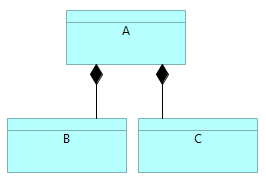

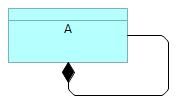

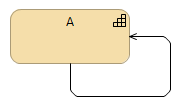

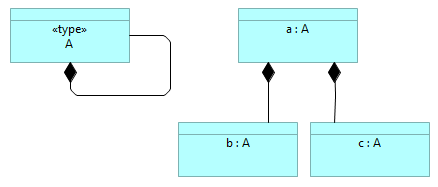

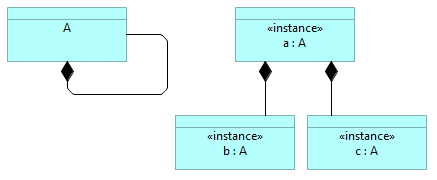

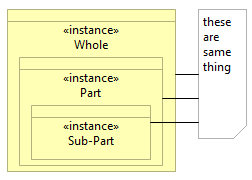

ArchiMate language does not distinguish between types and instances. Because among the enterprise architecture models there are both type and instance models (sometime it even makes sense to put both types and instances on the same model), some technique must be used to distinguish between types and instances. ...Recently I stumbled upon a strange „feature“ of ArchiMate language that brings some ambiguity into the models. In the ArchiMate specification (see Open Group ArchiMate 3.1) chapter 3.6 is written „The ArchiMate language intentionally does not support a difference between types and instances.“. This design decisions brings ambiguity into the meaning of the diagrams. For example, what is described inthe following diagram: Does this mean that:

There are situations, where it would be possible to deduce, whether diagram is describing the types or instances (because for example certain reflexive relationships, like „composition“, would not make sense for the instances), like: But in some cases it would be impossible to know without some indication of what kinds ofelements are in the model or on the diagram, like: Therefore indicate the usage of types or instances explicitly, using for example through ArchiMate specializations (similar to UML sterotypes) and the naming convention similar to UML, either for the types: or for the instances: Although in ArchiMate specification it is stated that „At theEnterprise Architecture abstraction level, it is more common to model types and/or exemplars rather than instances.“, there are still many cases where the model of the actual enterprise architecture consists of instances (like capability maps, process maps, or application landscapes, which all represent certain enterprise portfolios), and therefore it makes sense to clearly indicate on the diagrams, where are the types (for example when describing conceptual models or solution patterns) and where are the instances, especially if both are mixed on the diagram. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Hierarchies with the single elements and fixed levelsposted Nov 8, 2020, 10:58 PM by Alar Raabe

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

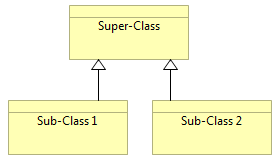

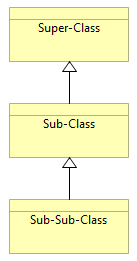

There is certain wish, when handling the hiertarchies, to fix the numer of levels, with the reasoning that this should make things simpler and clearer. This leads to the hierarchy levels which contain only single element, which could make sense in the class/type hierarchies, but does not have any meaning for the composition hierarchies. ...I have seen many times the wish to fix the number of levels in the decomposition hierarchies (like for example in the maps of business capabilities), with the reasoning that it would make things easier by always having known number of levels. One result of this approach is the appearance of branches with single elements on certain levels. There are such hierarchies, where the elements with just one sub-element will make sense, and there are other hierarchies, where this doesn’t make sense. For example in case of taxonomy, each element is representing a set of features – it is a class hierarchy. In the class hierarchy it makes sense to have even single sub-class for a particular class, because this sub-class represents a different set of features than its super-class. It also could make sense in class hierarchy, if needed, to have a fixed number of levels – because on each level of each branch you have different set of features (which you can distribute evenly). It makes sense to have: On the other hand, in case of functional decomposition,like hierarchy of business capabilities or application components, each element is a whole – it is a composition hierarchy. In the composition hierarchy(which consists of instances, not of classes) it doesn’t make sense to have an element that has only one part, because these are then the same thing. It makes sense to have: It also would not make sense in the decomposition hierarchy to have fixed set of levels – because this would either enforce the designers to come up with "dummy" levels just to follow the scheme, and results decomposition that is not natural, causing branches with single elements just to „fill“ the levels of hierarchy, introducing multiple ways to name what actually is the same thing. This is the reason I wouldn't advise to create for example business capabilities with only one sub-capability or application components with only one sub-component. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Using models in software development ...posted Jun 7, 2020, 4:30 AM by Alar Raabe [updated 4 Sept, 2023, 5:15 PM]

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Compared to the beginning of software engineering, the current practice tends to diminish or completely drop the use of models (formal represenation of requirements towards the software system). But if there's any wish to automate the software development activities beyond the simple pipelines of build tools, there is need for the strong formal models that specify what to automate. ...I see more and more, that the usage of models (referring to traditionally used qualitative, often graphical, models and modeling languages) and model building is diminishing in the software engineering (if we can talk about the software "engineering" anymore at all). The reason seems to be that developers do not want to use the models and therefore making or maintaining these is perceived as "no-value" overhead. Behind the reluctance of developers to use models is often the agile movement's argument that everything could be seen/found from the code, and because in DevOps same team that does the development, does also maintenance, there’s also no need to communicate between different teams. But actually:

Because additional information (same that has been traditionally represented by the models) is needed and because code isn’t usually very much commented and often also not very readable,so often developers and others, involved in the software development activities, try to find other ways to collect and maintain this additional information, representing it usually in non-formalized textual form in their work-organization tools (e.g. Confluence wiki and in Jira tasks). Additional reason to drop models in the software development in favor of informal textual descriptions, seems to be the inability to automate anything in software development process apart from the simple "automation" of build tools to manipulate software artifacts in correct succession (thing that has been around already past 60 years) – so there’s no perceived value to have requirements or high-level abstract knowledge about the software to be represented in machine-readable form. Today still a very big part of the development of business software is solving rather standard/common problems and is filled with the repeating tasks, which are very easily automated (like development of GUIs (where they are not the distinguishing factor), integrations, transformations, reports, etc.), and doing so would economize a lot of development time, but this will be only possible, if the requirements and high-level design would be formally specified and represented in a machine readable form. So, the main question is "Dowe want/need to automate also our software development activities?", or do we just want to automate only the various business activities and continue with manual software development? If we want to automate software development (i.e. digitalize the software development), we need a formal, machine readable, representation of requirements and high-level designs (with the focus on formalization and machine readability, not just some pictures with "boxes and arrows"), in the same way as for example to automate the credit origination, we need formal representation of customer, loan, collateral, sales process, involved business rules, etc. Lately the question of automating the development of software has turned towards AI (using large language models trained on the existing code). The problem with this approach is, that because the models developed by the machine learning are non human-readable and non-transparent to the users, the way to control and guide the generative AI is via prompts, which quickly becomes rathere similar problem as controlling and guiding the human developers through the natuaral language (which is ambiguous by nature). |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Business Capability – a short clarificationposted Jun 19, 2017, 2:54 AM by Alar Raabe

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

A "business capability" describes ability to perform certain set of related activities for providing a set of business, by combining people, processes, resources and governance. Business capabilities are connected to other business capabilities through the business services and form a value network. ...The term “business capability” is synonymous with BIAN “Service Domain” (see BIAN Practitioners Guide), with “business component”in IBM’s CBM methodology (see Component Business Models), and with “business function” in general business management. A “business capability” describes ability to perform certain set of related activities for providing a set of business services, by combining people, processes, resources(incl. needed technological systems) and governance, using the business services from other business capabilities, if needed. Where “business service” describes externally visible unit of business functionality of a business capability, which provides value to service consumers, is provided via explicit external interfaces, and realized by business processes. You can think of a business capability as a self-contained part of business that could be outsourced as is. Business capabilities themselves can be hierarchically sub-divided into smaller business capabilities if needed, or combined into larger business capabilities up to a business capability to provide all the services of a certain business (for example to provide all banking services). Business capabilities are connected to other business capabilities through the business services and form a value network. The business capabilities for a given business domain can be found/formulated, taking as the starting point the lists of key activities needed for all the business models of given business domain. The set of business capabilities describes what things given business domain must be able to do, to support the business strategy and execute the business models. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

API vs. ESB (and other related tools)posted Jun 16, 2017, 1:04 AM by Alar Raabe

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

I would like to clarify some questions related to API management, ESB and specific service interfaces. From one side, API (Application Programming Interface) is nothing more than a specification – a text, containing a set of more or less formal statements, which specify the available (service) operations and data that flows through the interface when these operations are performed. Therefore managing an API is nothing morethan managing any other formal document – which can be done using any basic text editor or something more fancy, called API management tool, with lots of bells and whistles and with heavy price tag. From another side, ESB is nothing more than a system that transports and routes service requests, and returns matching responses, usually providing several different physical mechanisms to do so, independent of how these service requests are defined or do they together at all form an API. Therefore, if we implement API management tool and ESB, then this will not in any way result in a specific API (or service interface). Developing a specific API is quite time-and resource-consuming task, which needs to be planned and designed as anyother large development. What makes API design even more important, is that API's guide the architecture of future developments and affect strongly their properties. A good analogy here is with DBMS and actual database schema – although we have tools for designing database schemas(e.g. ERwin) and DBMS to run these schemas (e.g. Oracle or TeraData), we cannot assume, that database schema (e.g. for Enterprise DW), suitable for current and future needs just emerges from separate developments. It needs a special (some-time very large) effort, to develop a suitable concrete data-base schema. API design and development requires same way as data-base schema design and development:

And the above mentioned artifacts are not produced neither by the API management tools nor by ESBs. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Thoughts on "Architect Your Business - Not Just IT"posted Apr 13, 2015, 8:23 AM by Alar Raabe

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

When reading MIT CISR Research Brief No 12 from 2014 "Architect Your Business - Not Just IT", I agree very much with the statement that “… despite the title, business architects rarely design their company’s business.”! The main puzzle for me is, that even when everybody in the organization sees and agrees, that “…their processes, structures, and systems are not providing the agility they need …” (i.e. the business architecture of the company is not adequate), I don’t usually see any dedicated effort for designing a new business architecture, not to mention employment of a specialist with business architect skills for doing that. Here I must agreeagain with the statement that “… the dominant design approach for large companies is ‘divide and conquer’ in which individual leaders accept responsibility for success over a specific set of closely related business activities.”. Because of the Conway's Law, this approach leads to a business and IT architectures that copy the power-structure of the organization. The above mentioned approach could work, but only if the domains of power and integration/interaction points between those separate “kingdoms” are very clearly defined and controlled, and designing these interfaces and controls should be the main task for the actual business architect. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Complexity in/of the enterprise architectureposted Dec 30, 2013, 2:10 PM by Alar Raabe

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The negative effects of the overall complexity of business and IT in the enterprise, manifest themselves as unreliability and excessive cost of operations, and excessive cost and time to make changes. Business complexity has additional negative effects due to the difficulties in selling more complex products and customer dissatisfaction due to unclear and time consuming business processes. Therefore complexity of the business and IT in enterprise needs to be controlled and managed. To be able to control and manage the complexity, we need to be able to measure it. If looking into different treatments of the complexity of systems, we can define the complexity as the number of different elements and their interconnectedness (number of interconnections between these elements). Based on such definition, we propose to measure business and IT complexity by counting the elements of business (like business models, customer segments, offered products, business functions, business services, business processes, etc.) and IT (like data stores, applications, technologies, etc.), and their interconnections. In both business andIT we can differentiate between:

The internal business complexity (e.g. how we organize or operate the business) defines also large part of the external IT complexity, the other part being defined by the external technological factors. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Extending EA meta-models to contain the environment ...posted Jul 29, 2013, 1:55 AM by Alar Raabe

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Current EA meta-models describe in great detail the internals of the enterprise, but leave the environment in which the enterprise operates either totally out, or describe it in considerably less detailed way. There are definitely some meta-models, for example Nick Malik's EBMM (contains Influencer) and new ArchiMate motivation extension (contains Driver), which try to deal with the (inconveniences) of outside world, but this is not that elaborate and structured, as these parts of meta-models which deal with inside world. If we see the role of EA function as supporting the orientation of the enterprise according to John Boyd's OODA loop, there is need to have sufficiently good models for both representing and interpreting the environment, and representing and interpreting the enterprise itself. We should add something similar to the dynamic financial analysis (DFA) models to the EA meta-models, to be able represent the impact of environment to the enterprise, as elements representing competition, markets, regulations, etc. (see for example A. Bergbauer, V. Chavez, T. Fischer, R. Perera, A. Roehrl, S. Schmiedl, Back to the future: Dynamic Financial Analysis (DFA) for decision making, 2004 (Fig. 3), or M. Eling, T. Partnitzke Dynamic Financial Analysis: Classification, Conception, and Implementation, 2005 (Fig. 2), or M. A. Taylor, Business Environment Model, 2013). |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Do/should we have "internal customers"?posted Jul 24, 2013, 2:53 AM by Alar Raabe

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

If we use in the enterprise architecture framework IBM Component Business Model (CBM) and A. Osterwalder's business model canvas (BMC) for describing the business and its parts in a business domainarchitecture. The CBM can be used to describe the overall business functionality and the functional decomposition of whole enterprise into business components, which can be viewed as small independent businesses. The business components in a CBM are connected through the business services that they produce and/or consume from the other business components, forming a value network. Some of those business services are produced and/or consumed by the external parties (including the enterprise’s customers). So from that viewpoint, for every business component, an external (to the given business component) party could be in two different role – customers/consumers of the produced services and suppliers/producers of the required services. The A. Osterwalder’s business model canvas can be used to describethe overall business logic of how the business works for whole enterprise, and/or for each functional sub-division down to the business components, identified in the CBM. Business model canvas also identifies external parties in two different roles – partners and customers. This separation is beneficial because business usually needs to employ different relationship management techniques for the external parties playing those different roles, and usually also the channels through which the value is delivered to the business, and through which business delivers value, are different. Above described conceptual models (together with their language) provide the modularity and encapsulation, needed to manage the inherent complexity of the business functionality that whole enterprise comprises. Employing this view in business organization/operations allows us to achieve self-optimization of the operations of whole enterprise by optimizing the operations of separate business components, and robustness by encapsulating the business components behind the well formed service agreements. In principle we should be able to separate and replace any business component (including IT or its parts) as an independent business entity, without changing the internal workings of that particular business component and affecting the operations of overall value network. So in the behavior of a business component, there should not be any difference, whether the external (to the given business component) party is also external to the whole enterprise or just another part of the enterprise, but the business component should definitely have different behavior (down to the clear service agreements) towards the parties to whom it delivers services and towards the parties that deliver services to it. To avoid confusions with the usage of word “partner” in the A. Osterwalder's business model ontology it would not be good to denote such business components, which do not directly deliver services to the enterprise’s customers, with the same word “partners”, for both consumers of their services and suppliers of services they need. There might be political reasons for which we want that in our language enterprise’scustomers should stand out from business components that are internal to the enterprise, and because the value network inside the enterprise uses different ways to account the value, the word “internal customer” might not be appropriate for consumers of internal services. So should we then use the word “consumer” throughout the enterprise architecture models/descriptions to denote the business service consumers in the business models instead of word “customer”? In case the same business component provides the same business service to both enterprise’s customers and other business components in the enterprise (as in many cases IT related business components do), should we treat those as two different service consumer classes, and use different words to denote these? |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Reducing the complexity and increasign the modularity ...posted Apr 22, 2013, 8:26 AM by Alar Raabe

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

... of enterprise systems, based on the results from (The Evolutionary Origins of Modularity), could be achieved, by imposing an additional cost (a kind of "tax") upon the direct connections between the enterprise systems. Reserves created from such "tax", could be invested into the improvement activities of enterprise architecture. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Controlling the enterprise (IT) architectureposted Feb 27, 2012, 11:10 PM by Alar Raabe

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

We can control/develop enterprise (IT) architecture by following:

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Measuring the Effect of Enterprise Architectureposted Nov 28, 2011, 09:25 AM by Alar Raabe

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Some things that can be measured for estimating/following the success of enterprise architecture activities:

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

About the requirements analysis ...posted Mar 12, 2011, 9:41 PM by Alar Raabe

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Because every requirement has a price attached (in terms of time and money), they should be handled with care and precision (as money is handled). |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

About freedom ...posted Mar 12, 2011, 09:17 PM by Alar Raabe

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

IT people use Android, but business people use Apple iOS. Both want freedom, but these are two different freedoms:

The same case is with the agility:

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

What system aspect is above others – who rules in governance ...posted Mar 03, 2011, 02:35 PM by Alar Raabe

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

I don’t want to put all the modeling disciplines into the information modeling (as sub-domains) just because most of these are somehow related to information modeling, or just because we can view any modeling activity itself as information processing activity. For me information modeling is part of the larger domain of modeling the structural aspects of the domains or systems, and answers in this context to the following questions:

It is important to have in mind that because different modeling disciplines cover different aspects of the system under study, we get the full holistic picture only by applying several modeling disciplines, not by putting one discipline above others – real world systems have both structure and behavior at the same time. That is why I would like to see that neither information owner nor process owner are ruling over each other in information or process governance – the governance should be set over full picture that describes all aspects of given domain or system (EA in case the system is the enterprise). To achieve the consistency, stability and encapsulation, there is no need to try to establish global governance over all levels, just higher level composition owner should govern the interfaces (incl. both structure and behavior) between the next level components – doing so we are able to partition the models to fight the complexity, and allow freedom of development/governance inside the components. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Business components solve problems of process-orientationposted Feb 20, 2011, 04:51 PM by Alar Raabe

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Most of the problems in process-orientation come from the fact, that processes are viewed as global artifacts independent and above of the functions (business components). Hence for example the problem of cross-functional processes and lack of authority of process owners in the organization. If we would build the whole enterprise using component-orientation -- that is to encapsulate the processes inside the business components, and allow only interactions of business components based on well-defined interfaces (SLAs), then there will be no such problems, as every process owner is in full control of its processes and resources needed to perform these. Additionally enterprise would be way more agile (and self-organizing), as responses to the possible changes are localized into the components, any components can be replaced with the best in industry (outsourced) without any adverse effects to business as whole, and the global flows of activities will adjust themselves to the optimal in given context. If you look from the customer's perspective, then processes are encapsulated inside the component with which you interact. For example if customer requests for loan offer from sales component, and receives the response from sales component, then it doesn't matter to him/her what other business components are involved and how. In this case sales component management is completely in charge of the process which is used to produce the response (or service), as it is not crossing borders of component, and component management has SLAs for all the services that it needs/uses from other components -- so there is no need for matrix-organization (with the dual and often conflicting command lines) at all. To the sales component doesn't actually matter how (using what process) the underwriting is done by the risk management component as long as the SLA for underwriting is not breached. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Software "stack" -- business logic and reusable assetsposted Feb 12, 2011, 11:01 AM by Alar Raabe

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Software "stack" -- separation of concerns:

(A business function is a function that gives business benefit to the user, it is often specified/described by a business use-case.) Guidelines for implementing and packaging business logic and reusable assets:

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

How to start describing business (architecture)posted Feb 09, 2011, 09:46 PM by Alar Raabe

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Specifications and actuals (and UML powertypes)posted Feb 09, 2011, 09:43 PM by Alar Raabe

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

What I have in mind, is the duality of concepts in the domain, where:

Both sets of concepts being on the same modeling level, and always have at least one-to-many relationships between each other. The difference of specification from the actual is, that specification can, and in many cases do exist without corresponding actuals. Also specifications have usually own behavior, which is different from behavior of actual. Participants of this (pattern?) could be represented in models using corresponding stereotypes, or just grouping these together on diagrams. This pattern has helped me to identify concepts/relationships, and to organize the model. Maybe this would be possible to model using UML powertypes, but I would avoid mixing different modeling levels (model, meta-model, ...) in the same model, and would prefer to use stereotypes instead of these (to show that certain classes are from given class denoted by stereotype). If we want to model the business rules for meta-model elements, then we should have a separate meta-model, that shows the specialized elements and respective rules/constraints attached to these. This distinction in modeling levels is good to be maintained also into the solution, down to the physical models -- that is if we choose to have dynamically configurable system, then from the meta-models we derive the physical models representing the configuration information, and from the models we derive the actual content of configuration information for the system. Failure to make this distinction clearly is the source of problems in maintenance of dynamically configurable systems. What Fowler describes as specification pattern seems to me too narrowly applied only for selecting objects from object sets, but maybe I am mistaken. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

On EA function and the "customer" of EAposted Feb 04, 2011, 09:53 PM by Alar Raabe

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Gartner Pub. "Develop Next-State Enterprise Architecture to Improve Usability" states: "Too many EA programs are suffering because their content is being largely ignored by some of the very people they are trying to serve -- project teams." Is it really so that EA program is trying to or must serve project teams? I would argue, that the main purpose of the EA programs is not to serve, but to constraint the project teams -- doing so of course in the name of serving the whole enterprise including the project teams, but still the main purpose is to impose the constraints that restrict the project teams. It is the same, as police is establishing speed limits for motorists -- for benefit of whole society some of the members need to be restricted in their doings. This of course doesn't mean, that restrictions/constraints developed by EA program, doesn't have to be "actionable" and "pragmatic". The detail level and overall nature of restrictions/constraints has to match the maturity of project teams -- by analogy, for small children the restrictions must be very precise and categorical, but when dealing with grown-ups you can rely on some level of common sense (or maybe not).<7p> ... The overall question is about the primary stakeholder/counter-party -- who EA function serves. Does the EA function serve management in development of enterprise, working for global goals, or does it serve the project teams, working for local goals? I would focus more on serving the management and global goals, because project teams are already served by the application architects. There was an important remainder in the article -- you can't have road map (next steps), before you have future state! |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||